5 Logical Fallacies from the Republican Debate

| | Cue Jeopardy music |

For those of you who aren't political junkies, there was a debate Monday night in New Hampshire between seven people trying to become 2012's Republican candidate for president. Plenty of thinkers, political writers, pundits, and others have treated the debate as the perfect opportunity for the public to get to know the candidates. For me, though, it is the perfect opportunity to revisit one of my favorite topics: how politics is a great primer for understanding bad logic. I have covered this subject twice before (here and here), but there are dozens of fallacies I haven't gotten to yet. Because of this, I not only watched the debate on CNN, but I rewatched it and rewatched it again, carefully sifting through two hours of political jabbering and posturing in order to catch the candidates in brand new lapses of logic. Please remember that I did this for you, dear reader.

Before I list my results, I'd like to explain an extra fallacy, the argumentum ad logicam, which is also known as the "argument from fallacy." This is the fallacy of arguing that, because someone's argument contains a logical fallacy, it must be false. It is absolutely possible to make a correct argument using poor logic. For example, you can argue that the world is round because over 99% of the world's population thinks it is, which though true, is a fallacious argument (the argumentum ad populum). I bring this up in a futile attempt to appease those of you who will accuse me of political bias, because it is important to remember that the mere act of pointing out the fallacies in these arguments is not the same as arguing for or against their authenticity.

So without further ado, here are five more fallacies, each with an example culled from the Republican primary debate on CNN Monday night.

THE POLITICIAN'S FALLACY

| | His plan is really something |

In order to justify their existence, nearly all politicians spend the majority of their time trying to convince their constituents that something needs to be done. They'll tell you sob stories, try to convince you that something bad is going to happen, and then go on to describe their plan to fix it. This, in and of itself, is not a bad thing. Often, something really does need doing, and on rare occasion, a politician actually gets it right and fixes a problem. However, nine times out of ten that a politician starts telling you that something needs to be done, that politician can't come up with--or doesn't want to fully explain--the solution to the problem. When this happens, he or she resorts to the politician's fallacy.

This very specific form of the "fallacy of the undistributed middle" is incredibly easy to spot. The general argument goes: (a) something must be done; (b) this proposal is something; (c) therefore, this must be done. Politicians don't even try to disguise it. On Monday night, it was former Minnesota Governor Tim Pawlenty who tried to use this one. The subject was Medicare, and Pawlenty was emphatically trying to explain that the program was quickly approaching insolvency and that people were going to start losing Medicare coverage as early as 2014. He mentioned that he had his own plan and then rhetorically asked, "If it was a choice between Barack Obama's plan of doing nothing?" The moderator, John King, didn't give Pawlenty time to find the correct grammar or finish the thought, but we all know where it was going.

The talking point Pawlenty was trying to repeat, which many Republican leaders have been putting out there, is that any plan to "fix" Medicare (usually referring, implicitly or not, to Representative Paul Ryan's 2012 budget, though Pawlenty was indicating his own plan) is better than President Obama's plan, because Obama's plan is "doing nothing." In other words, because something needs to be done about Medicare and because a Republican plan is not nothing, a Republican plan needs to be done. It's a classic example of the politician's fallacy.

ARGUMENT FROM AUTHORITY

| | Don't take her word for it |

Sometimes, a politician can't convince you that he knows what he's talking about, so he has to cite other people that you might trust more. Again, this is not necessarily a bad thing. It's nice to have statistics or other authorities to back you up. In fact, in politics, if you can't come up with any authoritative support for your positions, you're doomed. So when a politician cites other sources, he will often treat his authoritative source as incontrovertable. If that source indicates something that backs the politican up, the politician will treat that indication as fact, even though it is usually just opinion.

This is a fallacy known as the argument from authority. In logic, any argument that puts undue stress on the reliability of an authority is a fallacy, and typical examples include mentioning how a source is authoritative on one subject to bolster an argument unrelated to that subject. For instance, it would be fallacious to say that Al Gore's Nobel Prize means that his opinion of who will win the Stanley Cup is more valuable than your own. A source can be authoritative on the subject at hand, though, and still be used fallaciously, as was demonstrated Monday night by Minnesota Representative Michelle Bachmann.

While discussing the possible repeal of President Obama's health care law if she wins the presidency, Representative Bachmann said, "The CBO, the Congressional Budget Office, has said that Obamacare will kill 800,000 jobs. What could the president be thinking by passing a bill like this, knowing full well it will kill 800,000 jobs?" While it is true that both major political parties tend to trust the CBO and that the CBO tends to be fairly accurate, its reports are not facts. When it comes to PPACA ("Obamacare"), the CBO admitted to having great difficulties in making conclusions because the law is so complex and its ultimate results are, at best, unpredictable. This makes its statements about the law tentative, not definitive, but Representative Bachmann treated one of those statements as gospel, arguing that the President had to have known "full well" that the statement was true.

HASTY GENERALIZATION

| | All pizza toppings are pepperoni |

Let's say you can't convince people that you know what you're talking about and you can't cite a source authoritative enough for people to defer judgment. When this happens, you might resort to the tactic of painting your political opponents with broad brush strokes. If you can convince people that an entire group think and feel in a way that is not theirs, you can get them to conclude that you are more preferable to members of that group. This is the bread and butter of politics, saying that all liberals or all conservatives behave the same way, but it is also one of the more dangerous logical fallacies out there.

It's called the hasty generalization. Whenever you make a statistical conclusion based on a tiny sample size, you are guilty of the fallacy. What makes it dangerous is that this is the intellectual seed for stereotyping, prejudice, bigotry, and racism. In politics, hasty generalizations are almost entirely responsible for polarizing people whose political opinions aren't all that different. It makes it easy for people to believe that everybody on the opposing side is unified in opposing their beliefs, but this is never actually true. In a sense, this is why people occasionally take politics so seriously and get into such vitriolic debates over the smallest of perceived slights. However, on Monday night, the most obvious hasty generalization wasn't about political party; it was about religion.

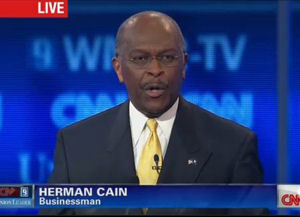

Businessman Herman Cain said:

I would not be comfortable [with a Muslim in my administration] because you have peaceful Muslims and then you have militant Muslims, those that are trying to kill us. And so when I said I wouldn't be comfortable, I was thinking about the ones that are trying to kill us, number one. Secondly, yes, I do not believe in sharia law in American courts. I believe in American laws in American courts. Period. There have been instances in New Jersey. There was an instance in Oklahoma where Muslims did try to influence court decisions with sharia law. I was simply saying very emphatically American laws in American courts.

Cain's argument is muddled, but the implication is fairly clear. He is essentially arguing that Muslims, as a general rule, want to inject sharia law into American courts, which is why he "would not be comfortable" putting a Muslim in his administration. It's an absolutely ludicrous (and offensive) statement, but it's also a hasty generalization.

POST HOC ERGO PROPTER HOC

| | Mitt Romney spoke after Ron Paul, which means Ron Paul is responsible for Mitt Romney |

Post hoc reasoning is a form of argument that assumes causality based on chronology. If something happens after something else, the previous event must be responsible for the more recent one. Many superstitions are based on post hoc thinking, like assuming that something bad will happen after you walk under a step ladder just because it happened once before. The thinking is that the bad thing only happened because you walked under the step ladder.

Politicians use post hoc reasoning to point to results. Again, this is to justify their existence. They want you to believe that whatever needed to be done was done by them. They want to take credit for all the good things going on today by saying they are the direct results of legislation, leadership, or other things they put into action yesterday. Conversely, a politician will use the post hoc fallacy to blame the actions of opponents for anything bad happening today.

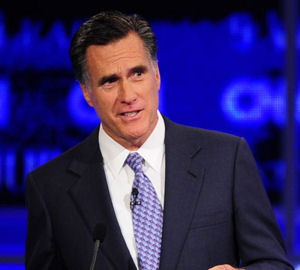

Former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney demonstrated this one (along with the fallacy of the single cause) when he said, "Now we have more chronic long-term unemployment than this country has ever seen before, twenty million people out of work, stopped looking for work, or in part-time jobs that need full-time jobs, we've got housing prices continuing to decline, and we have foreclosures at record levels. This president has failed." He is saying that the president's previous actions are responsible for all these bad things happening today. Granted, you could argue that it is the president's job to ensure that these bad things don't happen and thus "this president has failed," but that's not the argument Romney was making. His argument was more along the lines of: (a) Barack Obama was elected president in 2008; (b) the economy has sucked since 2008; and therefore (c) Barack Obama is responsible for the sucky economy of today.

CUM HOC ERGO PROPTER HOC

| | Let's see him talk his way out of that hair |

Similar to post hoc reasoning, and often mistaken for it, is cum hoc ergo propter hoc, which is the assumption that one thing must be causing another just because a relationship between them can be identified. For example, there is a positive correlation between shoe size and intelligence, but it would be a fallacy to argue that your shoe size determines your intelligence (it's actually your age--when you're young and stupid, you have small feet). This is a common fallacy in science, leading to the much repeated maxim "correlation does not equal causation."

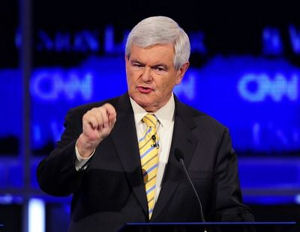

Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich fell victim to the cum hoc fallacy during the debate. This one is extremely subtle, though, so read the quote carefully and see if you can pick up on it. When asked if the government should continue to fund space travel, Gingrich said:

NASA has become an absolute case study in why bureaucracy can't innovate. If you take all the money we've spent at NASA since we landed on the moon and you applied that money for incentives to the private sector, we would today probably have a permanent station on the moon, three or four permanent stations in space, a new generation of lift vehicles, and instead what we've had is bureaucracy after bureaucracy after bureaucracy and failure after failure.

Aside from being highly speculative, Gingrich's statement is fallacious in that he is arguing that the current decline of NASA has come about only because of "bureaucracy." He is arguing that, because NASA is a publically funded organization and because it is currently declining, government funding necessarily causes decline. In truth, one can point to hundreds of different factors that are responsible for NASA's decline, but to argue that the government is responsible for it just because the government is involved in it is illogical.

Keep in mind that this is just a sampling of the many fallacies made on Monday night. Once you know what to look for, you can find at least one fallacy in practically every statement a politician makes. This is regardless of party affiliation, regardless of subject matter, and regardless of whether or not the conclusions being made are correct. However, as I've pointed out before, these fallacies are rarely ever intentional, because politicians, just like the rest of us, tend to think illogically. It takes years and years of practice to reduce the amount of poor logic in your thinking, but nobody, no matter how smart, is capable of getting rid of it all. It's just that it seems so much more prevelant in politics, probably because, when it comes to politics, we spend more time rationalizing opinion than we spend coming to unbiased, empirical conclusions.

-e. magill 6/15/2011

|

|